Analytics, Competition, Construction, Energy Market, EU – Baltic States, EU – CIS, Gas, Gas Market , Russia, Transport, Ukraine

International Internet Magazine. Baltic States news & analytics

Wednesday, 04.03.2026, 22:15

The real story behind Nord Stream 2

Print version

Print version |

|---|

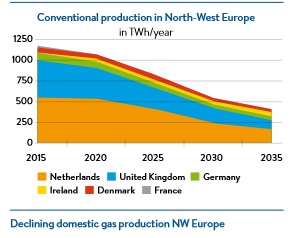

The story behind Nord Stream 2 starts with an incontrovertible fact: domestic gas production in North West Europe is declining. The scale and speed of the decline can be seen in this chart:

How can the countries respond to this development? They can do to three things: 1) develop their shale gas resources 2) cut back on consumption or 3) increase imports. Countries like Germany and France do have shale gas, but they don’t allow fracking for environmental reasons. The UK government is trying to stimulate fracking, but so far is has not been able to take off because of public opposition.

Cutting back on consumption seems a more feasible option. EU

gas demand actually fell from a peak of some 530 bcm in 2010 to a low of 409

bcm in 2014, mostly as a result of the economic crisis. Last year, demand

rebounded to 426 bcm, according to figures from trade association Eurogas.

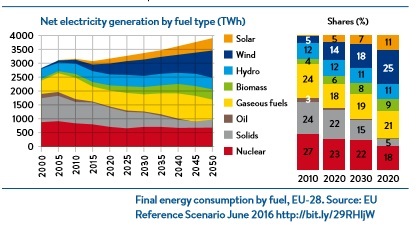

Nevertheless, even though no one can predict how European

gas demand will develop, most analysts believe that natural gas will continue

to play a significant role in European energy demand. There are two reason for

this: first, reform of the EU’s emission trading system (ETS) will lead to

steadily rising CO2-prices, which will drive coal-to-gas switching in the

electricity sector. Second, renewable energies will show strong growth, but

will still need to be complemented and backed up by gas.

These are precisely the reasons why the European

Commission’s Reference Scenario, which is the main energy modelling tool

Brussels relies on in all its energy policies, projects that the share of gas

in final energy consumption will stay relatively stable up to 2050

This then leads Europe to the third option: to increase its

gas imports.

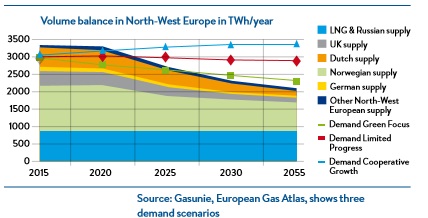

Obviously as a result of the decline in domestic production,

North West Europe is faced with a growing “import gap”. The European Gas Atlas,

published by Dutch gas infrastructure company Gasunie, illustrates this

situation as follows:

This growing import gap is what the business case of Nord

Stream 2 is built on. It is the gap that Gazprom is eager to fill with the new

pipeline.

Currently the share of Russian gas in European consumption

is less than 30%, with EU domestic production, imports from Norway and

other countries accounting for more than three-quarters. If this figure goes

up, European “dependence” on Russia will increase.

But Gazprom’s “dependence” on Europe is actually greater

than European dependence on Gazprom. The Russian company relies on Europe for

almost two-thirds of its sales revenue and almost half of its sales volume

(figures first half of 2016). And although Gazprom is expanding in Asia, Europe

is and will remain by far the largest market for the Russians for a long time

to come.

Gazprom’s heavy reliance on the West-European market is

precisely why the company decided some years ago that it wanted to diversify

its routes to Europe. Gazprom has more than once encountered major problems

with its gas transit through Ukraine, which until recently was one of the two

major routes to the North-West European market. On several occasions,

especially in 2006 and 2009, gas transit through Ukraine was halted after

payment disputes with Naftogaz, the Ukrainian operator.

To reduce its dependence on its Central European routes,

Gazprom – with a number of Western European partners – built the (first) Nord

Stream connection, consisting of two pipelines, which became operational in

2011 and 2012, running through the Baltic Sea straight from Russia to Gazprom’s

largest market, Germany, avoiding Ukraine. Gazprom at this time also launched a

project, South Stream, to build a new connection to South-Eastern Europe (Italy

is another major export market), but it cancelled this after the European

Commission had indicated it did not fully conform with the requirements of EU

energy legislation. The Russians are now in talks with the Turkish government

to build a new connection from Russia to Turkey called Turkish Stream. Turkey

is one of the largest consumers of Russian gas, with Germany and Italy, and

could also function as transit route to south eastern Europe.

Right after the completion of Nord Stream, in 2011, Gazprom already started exploring the possibility of building another pipeline through the Baltic Sea. This resulted in the announcement, in September 2015, of a shareholders’ agreement between Gazprom and Shell, Eon, OMV, Engie and BASF/Wintershall to construct a second Nord Stream alongside the first.

European commison

Nord Stream 1’s two pipelines have a combined capacity of 55

billion cubic metres (bcm). Nord Stream 2 will have the same capacity. To put

this in perspective: a country like Germany uses roughly 80 bcm per year.

Many policymakers in the EU – particularly in Eastern

Europe, but also in Brussels – greeted the announcement of Nord Stream 2 with

alarm. Eastern European leaders charged that the new pipeline would negatively

impact energy security in their region, particularly in those countries that

are heavily dependent on Gazprom for their gas supplies.

The European Commission took the same line. Maros Šefčovič,

Vice-President of the European Commission in charge of the Energy Union, said

that “Nord Stream 2 could alter the landscape of the EU’s gas market while not

giving access to a new source of supply or a new supplier, and further

increasing excess capacity from Russia to the EU.”

But the energy security argument seems forced. Even if Nord

Stream 2 does not bring additional supplies (Gazprom says it will, opponents

deny this), all it does is change the route by which Russian gas is transported

to Europe. This does not reduce the number of routes or supplies, so how can it

reduce competition or energy security?

True, some EU markets, in particular Germany, will see their options to source gas improve, while the existing transit countries will face additional competition if they want to source Russian gas. However, for the EU market as a whole, this should not be a problem. That is to say: if the EU market functions as an integrated whole.

German prices

Here is where we come to

a key point in the Nord Stream 2 debate. Most analysts agree that the EU market

today is totally different from what it was ten or even five years ago. The

European Commission, with the help of far-reaching legislation, especially the

Third Energy Package (from 2009), has managed to create an integrated,

competitive gas market in the EU. There are rules requiring pipeline operators

to allow third-party access. Destination clauses have been banned. Ownership

unbundling has become mandatory. In addition, gas trading hubs have been

created, new pipeline interconnections have been built and reverse flow

capacity has expanded.

As a result, most independently analysts today would agree

that gas that enters the EU market at any point can be easily transported to

almost any other point.

Indeed, this is precisely what seems to have happened with

the gas coming from Nord Stream 1, according to Andreas Goldthau, Professor of

Public Policy at Central European University. “Particularly in Central Eastern

European markets significant shifts happened in the aftermath of Nord Stream

coming online”, Goldthau has written. “Gas flows started to reverse. While

traditional gas would travel from East (Russia) to West (transiting

Ukraine/Belarus and feeding Slovakia/ Poland), West-to-East trade picked up.”

Goldthau points out that after Nord Stream 1 became

operational, gas prices in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) “started to align

with German prices”. He

believes that Nord Stream 2 may be expected to further

reinforce this effect on the gas market: “Nord Stream 2 stands the chance of

enhancing the liquidity of regional hubs in which the additional volumes will

be primarily absorbed….Russian gas may end up competing with Russian gas.”

Goldthau does add that this does not yet apply to the whole of Europe. Parts of South-Eastern Europe are still isolated from the overall EU market as a result of insufficient infrastructure. In a report published in August 2016, “Completing Europe”, the US-based Atlantic Council admonishes the EU to complete the Action Plan for Central and South Eastern Connectivity agreed in Dubrovnik in July 2015 to end the isolation of this region. The plan includes the construction of several interconnectors as well as an LNG terminal in Croatia. The Atlantic Council also argues that Europe should build a “robust North-South Interconnector to link the Polish LNG terminal at Swinousjscie with Croatia’s planned LNG terminal at Omisalj in the Adriatic.”

Transit cost

It’s

safe to say that completion of the internal EU gas market would go a long way to

solving the problem of overdependence on Russia that persist in some Eastern

European countries.

Of course, it is still a bitter pill for existing transit

countries, such as Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine, to see their gas transit

income reduced. For Gazprom, however, the Nord Stream route simply makes

economic sense. According to Paul Corcoran, Financial Director of Nord Stream 2

(who held the same job with Nord Stream 1), transit through Nord Stream 1 is

already cheaper than through Ukraine. “The transit cost of Nord Stream 1 is

€1.86 per 1,000 cm per 100 km. For Ukraine it is €2.26 per 1,000 cm per 100 km.

And as Gazprom is half owner of Nord Stream 1, half of the cost comes back to

the company in the form of dividends. Not to mention that Ukraine have proposed

to more than double their tariffs. But it is also in the interest of European

consumers that gas is delivered via the most cost-efficient route.”

Corcoran expects that transit costs for Nord Stream 2 will be similar to those of Nord

Stream 1. He adds, “It angers me when I read statements that Nord Stream 2 is expensive and uneconomic. It’s not. Looking to the future it’s a very good investment.”

What about the geopolitical dimensions of Nord Stream 2?

There is no denying that the political situation around Ukraine and the EU’s

relations with Russia have changed for the worse after the Russian invasion of

the Crimea in 2014. But the question is whether that is an argument for the EU

to try to stop Nord Stream 2. There are many economic relations between Russia

and Europe going on (think of oil deliveries!) but no one advocates ending them

because of geopolitical tensions.

Gazprom is routinely accused by critics of “using gas as a political weapon”, but the question is whether that is true. Katja Yafimava, Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, asserts in article for the Istituto Affari Internazionali (December 2015, http://bit.ly/2ceoFhz): “There is no evidence at present that Gazprom cut or reduced supplies in the past to those European countries that were paying for their gas imports in full and on time at a price specified in their contracts, which makes the assertion that Russia has used the gas weapon towards European countries problematic.”

Likewise, Marco Siddi, Senior Research Fellow at the Finnish

Institute of International Affairs (FIIA) has written that “the claim that

Russia’s pipeline politics constitutes a geopolitical threat for Europe is

exaggerated.” Tim Boersma, Fellow in Foreign Policy at the US-based Brookings

Institution, has described “concerns about Russian gas” as “a relic from the

past”, given the changes in the European gas market.

In any case, even if some policymakers in Brussels or some EU member states regard Nord Stream 2 as a geopolitical issue, this does not necessarily mean they have the legal means to stop the project. As Severin Fischer, Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich, has written: “in a community that is based on the rule of law, the rule of law should apply to all actors in the same way. In the end, this means, that economic activities in the range of the legally defined framework should be assessed under the existing regulatory criteria, but not under normative categories of good or bad”.

Within budget

Paul Corcoran makes the same point.

“Political processes should be disconnected from the legal framework”, he says.

“The legal framework for Nord Stream 2 is the same as that for Nord Stream 1.

It is based on UNCLOS (the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea),

which gives the right to lay cables and pipelines on the seabed in Continental

Shelf areas. Nord Stream 2 will pass through the Continental Shelfs of five

countries and the territorial waters of Russia, Germany and a small part of

Denmark. If we obtain the required environmental permits, we will get

permission from these countries to build the pipeline, just as we did with Nord

Stream 1.”

Nord Stream 2 will submit permit applications in early 2017. Corcoran is confident that they will be able to obtain the permits at the end of 2017. At the end of 2019, Nord Stream 2 should be operational, according to plan. “We built Nord Stream 1 on time and within budget. We will do the same with Nord Stream 2.”

«The Baltic Course» Is Sold and Stays in Business!

«The Baltic Course» Is Sold and Stays in Business!