Analytics

International Internet Magazine. Baltic States news & analytics

Tuesday, 20.01.2026, 11:32

Modern EU policies: integration in action

Print version

Print version

The first volume can be seen here.

Volume 2. EU’s efforts to stimulate growth

and investment

Introduction. The second volume in the series on modern EU policies is devoted to recent EU intuitional efforts to streamline employment, increase growth and stimulate investment in the real economy. Therefore, the included information covers such spheres of the EU’s integration as youth entrepreneurship, SMEs support and activating investment process, to name a few.

New Commission – “new efforts” for boosting growth

In the Commission’s political guidelines, published in summer 2014, number first priority (out of total ten) was formulated as “a new boost for jobs, growth and investment”.

The newly nominated Commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker underlined that the first priority would be to strengthen Europe’s competitiveness and stimulate investment for the purpose of job creation.

In fact, within the first months of the Commission’s mandate, alongside the context of the Europe 2020 strategy, an ambitious Jobs, Growth and Investment Package was presented.

The Commission expressed intention to make much better use of the common EU budget and of Union financial instruments, for example, that of the European Investment Bank (EIB). These “EU’s public funds” have to be used to stimulate private investment in the real economy.

The member states need smarter investment, more focus on new technologies, less regulation and more flexibility when it comes to the use of these public funds.

In the Commission’s view, the strategy should allow the EU states to mobilise up to € 300 billion in additional public and private investment in the real economy over the next three years.

However, the whole investment environment has to be improved and fund absorption needs to be strengthened. The preparation of projects by the EIB and the Commission should be intensified and expanded. Thus, new, sustainable and job-creating projects that will help restore Europe’s competitiveness need to be identified and promoted. To make real projects happen, both the EU and the member states have also to develop more effective financial instruments, including in the form of loans or guarantees with greater risk capacity. A further increase in the EIB’s capital should be considered by the member states.

The Commission underlined that focus of this additional investment should be in infrastructure, notably broadband and energy networks as well as transport infrastructure in industrial centres; education, research and innovation, as well as the renewable energy. A significant amount should be channelled towards projects that can help get the younger generation back to work in decent jobs, further complementing the efforts already started with the Youth Guarantee Scheme, the implementation of which must be accelerated and progressively broadened.

The mid-term review of the Multiannual Financial Framework, scheduled for the end of 2016, should be used to orient the EU budget further towards jobs, growth and competitiveness.

As regards the use of national budgets for growth and investment, we must – as reaffirmed by the European Council in June 2014 – respect the Stability and Growth Pact, while making the best possible use of the flexibility that is built into the existing rules of the Pact, as reformed in 2005 and 2011. Commission’s concrete guidance was concentrated on the ambitious “Jobs, Growth and Investment Package”.

It is seen that jobs, growth and investment will only return to Europe if the EU would create the right regulatory environment and promote a climate of entrepreneurship and job creation. Hence, the innovation and competitiveness would not be stifled with too prescriptive and too detailed regulations, notably when it comes to small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). SMEs are the backbone of the member states’ economy, creating more than 85% of new jobs in Europe and they have to be free from burdensome regulation.

This is why the new Commission entrusted the responsibility for better regulation to the first Commission Vice-President (Frans Timmermans) while giving him a mandate to identify, together with the Parliament and the Council, “red tape” both at European and at national level that could be swiftly removed as part of jobs, growth and investment package.

Source: ttp://ec.europa.eu/priorities/docs/pg_en.pdf#page=6

Governments and social partners’ role

Tripartite Social Summit in mid-2014 urged the EU member states’ governments and social partners towards creating more jobs and stimulating investment to provide growth.

EU leaders and social partners have agreed on the urgent need to stimulate investment and create more jobs in order to meet the objectives of the EU-2020 Strategy, the EU's long-term growth and jobs plan.

The European Tripartite Social Summits (which takes place

twice a year, ahead of the spring and autumn European Councils), gather workers'

and employers' organisations in Europe (so-called social partners) together

with the President of the European Commission, the President of the European

Council, the EU Heads of State and Government, and Employment Ministers from

the countries holding the current and future Council Presidencies. The social

summit in 2014 agreed on the need to pursue reforms to support a long-term

recovery; the participants also discussed general issues concerning the EU's

economic governance within the European Semester.

The Tripartite Social Summit is an opportunity for an exchange of views between European employer and employee representatives (the social partners), the Commission, as well as with the EU-level employer and employee representatives: the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC); BUSINESSEUROPE; the European Centre of Employers and Enterprises providing Public services (CEEP); and the European Association of Craft, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (UEAPME).

The Tripartite Social Summit discussed the Commission's recent strategy for the EU development up to 2020 (Europe 2020 strategy, see MEMO/14/149) and the mid-term review of the European Semester. The talks also focused on promoting a job-rich recovery, namely on ways to foster youth employment, and the social partners’ key role in this (see MEMO/14/571), as well as their importance in designing and implementing reforms at European and national level.

The official Commission’s communiqué underlined that over the last 10 years, the EU has helped to support investment in the EU – from negotiating the Multiannual Financial Framework, the EU's €1 trillion budget, to working with the European Investment Bank to get the most out of it.

The Commission argued that in “wanting to boost growth and jobs, EU countries also needed to reform their economies so they can compete with the rest of the world and attract companies willing to invest”. The commission was of the opinion that being serious about reaching the EU-2020 growth and jobs targets, the member states must be as well serious about reforms: the EU would provide help, but all EU countries must play their part.

For example, referring to the mid-term period from the EU-2020 strategy and the role of employer and employee organisations at European level, the Commissioner L. Andor underlined that investment in human capital was particularly important to support the European economy and ensure its competitiveness. He added that social partners both at EU and at national level must be fully involved in efforts to address the implementation gap, to pursue reforms and to increase national ownership of the Europe 2020 process.

Reference: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-1195_en.htm

For more information on the issue see the following websites:

= European social dialogue, and

Efforts to increase employment

In January 2014,

the Commission proposed improvements in European employment; it underlined that

the pan-European job search network

EURES would be strengthened to provide more job offers, increase the likelihood

of job matches and help employers, notably in SMEs, to fill job vacancies

faster and better, under a proposal presented by the European Commission.

The proposal

was adopted by the EU's Council of Ministers and the European Parliament, as it

would help citizens to make the most informed choice possible when it comes to

moving abroad for work.

The proposed EURES Regulation is one in a series of measures to facilitate free movement of workers. Already in April 2013, the Commission proposed to improve the application of workers' rights to free movement (see IP/13/372, MEMO/13/384) , as well as the EU's Council of Ministers and the European Parliament Communications in November 2013 on free movement of people (see IP/13/1151, MEMO/14/9).

About 7.5 million Europeans work in another member state presently, which is only 3.1% of the total labour force. Around 700,000 people on average move every year to work abroad within the EU, a rate of about 0.29% (!), which is much lower –5 times- than those of Australia (1.5% between 8 states) or almost 10 times lower than in the US (2.4% between 50 states).

The European Vacancy Monitor shows that despite record unemployment in Europe, 2 million vacancies were open in the first quarter of 2013. While the existence of open vacancies is a feature of labour markets dynamics, a significant part of these open vacancies may be due to labour shortages, which cannot be overcome locally.

The then EU Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, highlighted that the proposal represented “an ambitious step to fight unemployment in a very practical way”. It would help to address imbalances on labour markets by maximising the exchange of available job vacancies throughout the EU and ensuring a more accurate match between job vacancies and job seekers. “The reformed EURES would facilitate labour mobility and contribute to achieving a truly integrated EU labour market", the Commissioner added.

Reference: Improving EURES job search network, in:

http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-26_en.htm.

Commission proposed new rules. The

new rules would make EURES more efficient,

recruitments more transparent and cooperation among Member States stronger,

notably by allowing EURES to:

= offer on the EURES web portal more job vacancies in the EU, including those from private employment services. Job seekers all over Europe would have instant access to the same vacancies, and registered employers would be able to recruit from an extensive pool of CVs.

= carry out automatic matching through job vacancies and CVs.

= give basic information on the EU labour market and EURES to any jobseeker or employer throughout the Union.

= offer candidates and employers mobility support services to facilitate recruitment and integrate workers in the new post abroad.

= improve coordination and information exchange on national labour shortages and surpluses among Member States, making mobility an integral part of their employment policies.

These improvements would benefit jobseekers and businesses of all sizes, but particularly SMEs, since currently they may not be able to afford to recruit abroad without the services that EURES provides free of charge.

EURES service. Mobility has

significantly increased during recent years; thus, since 2005, the number of EU

workers active in another Member State has increased up to 4.7 million. Furthermore,

mobility intentions have also risen: the number of jobseekers registered on the

EURES portal has jumped from 175,000 in 2007 to 1,100,000 in 2013.

Set up in 1993, EURES is a co-operation network between the European Commission and the Public Employment Services of the EU Member States, plus Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, and other partner organizations. It has more than 850 EURES advisers that are in daily contact with jobseekers and employers across Europe.

The network also operates through the EURES portal. The portal is unique in the EU as it is free of charge and gives information on living and working conditions in all participating countries in 25 languages. The portal allows access to more than 1.4 million job vacancies and 1.1 million CV's at any time in a given month.

The EURES network accounts for approximately 150,000 placements per year (50 000 through its advisers and 100 000 through its portal).

EURES: purpose and functions.

EURES

(the abbreviation stands for “European jobseeker mobility network”) is a

cooperation network between the European Commission and the public employment

services (PES) of the European Economic Area (EEA) member states (the EU-28

states plus Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein) and other partner organisations.

Switzerland also takes part in EURES cooperation.

The EURES network, set up in 1993, is responsible for exchanging information and enabling cooperation among its stakeholders in order to help make free movement of workers a reality. EURES promotes mobility and reduces barriers to workers by contributing to the development of a European labour market that is open and accessible for all, ensuring the exchange of vacancies and job applications and transparency on labour market information.

EURES provides free assistance to jobseekers wishing to move to another country and provides advice on living and working conditions in the EEA. It also assists employers wishing to recruit workers from other countries and in cross-border regions.

Organisationally, the EURES consists of two principal components:

= the network of employment officers which provides information, guidance and support to jobseekers wishing to work in other Member States and employers looking to recruit suitable candidates from other Member States; and

= the EURES web-portal which provides access to job vacancies and is a real one-stop-shop for information on job mobility in Europe. It provides a range of other useful tools to help people make informed choices on the opportunities available.

Mobility in Europe: facts and figures. Free

movement of people is one of the fundamental freedoms in the European Union; according

to a Qualitative

Eurobarometer study conducted in 2010, it is the right that the EU

citizens cherish most; they consider it virtually synonymous with their status

as EU citizens.

It is enshrined in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (art. 21 and 45 TFEU). The Treaty itself and the Charter of Fundamental Rights confer directly to EU citizens the right to move and reside freely within the Union, together with a right to equal treatment, as part of their status as citizens of the Union.

According to the EU Labour Force survey (EU-LFS), in the second quarter of 2013, there were around 7.8 million EU citizens economically active in another EU country, representing 3.2% of the EU labour force. This represents a substantial increase compared to 2005 (around 4.8 million in 2005, or 2.1% of the EU labour force) driven notably by the 2004 and 2007 enlargements. However, the economic crisis has led to a decrease in mobility flows between EU countries: during 2009-11, intra-EU mobility flows dropped by one third, compared to the 2006-08 period.

Moreover, those aggregate estimates do not include all EU mobile citizens because the EU-LFS covers mainly people who are 'usually resident' in a country and not for instance, the most recent movers or the short-term mobile workers (e.g. staying only a few months).

According to the 2009 Eurobarometer on geographical and labour mobility, around 10 % of EU citizens declared that they had already worked and lived in another country at some time, with 51 % of them having worked for less than two years, and 38 % for less than one year. According to the 2011 Eurobarometer on the Single Market, 28% of the EU working-age citizens would consider working in another EU country in the future. Moreover, this share is particularly high (54%) among the young people (15-24) and among those aged 25-39 (38%).

International comparisons (e.g. OECD Economic Survey in EU, 2012) indicate that cross border mobility between EU Member States is limited compared to other regions (such as United States, Canada, and Australia). Although this can be partly explained by the very wide linguistic diversity and various institutional frameworks, these comparisons still suggest that more scope exists for higher geographical mobility in the EU. Moreover, the massive gaps currently existing between EU countries and regions in terms of unemployment rates and job vacancy rates are another sign that the potential of geographical labour mobility is insufficiently tapped. It is seen, e.g. in the staff working document on Labour Market Trends and Challenges accompanying the Commission's April 2012 Employment Package.

Current levels of mobility are still relatively low compared to the EU potential and not commensurate to what could be expected within a genuine single EU labour market.

Commission’s efforts to encourage

intra-EU labour mobility. Limited geographic mobility was identified in the

2012 Annual Growth Survey as one of the reasons for the structural mismatch

between supply and demand for labour, thus hindering recovery and long-term

growth (see IP/11/1381).

In the current situation of high unemployment and strong divergence across the EU member states, labour mobility can play an important role. Significant numbers of unfilled vacancies in high growth areas coexist today with high unemployment in other parts of the EU. Labour mobility can alleviate the pressure of employment in countries affected by the crisis while responding to the needs of the labour market where there is a high level of labour demand. According to Eurostat, while unemployment rates in November 2013 were around 5-6% in Luxembourg, Austria and Germany, they were close to 15-19% in Portugal, Cyprus and Croatia and higher than 25% in Spain and Greece.

Intra-EU labour mobility can help to address imbalances and support employment, whilst restoring dynamism and alleviating social suffering. Mobility can also help to kick-start recruitment drives and meet the needs of numerous employers by providing them with the skilled workforce they seek. Workers for their part can gain from a positive transition into employment.

Many studies have showed in the past the overall positive impact of mobility for both workers and firms. For instance, post-enlargement mobility is estimated to have increased the GDP of EU-15 countries by around 1% in the 2004 to 2009 period.

= A Lisbon job fair leads to a job in the Netherlands

Pedro Pereira, a Portuguese electrical engineer made redundant as result of the crisis, found a new position in the Netherlands through a job fair in Lisbon.

= A successful Job Day: 500 new contracts in four countries

A recent job fair in the German city of Saarbrücken, close to the French border, brought together over 6 500 visitors and led to 500 new placements and contracts.

= Assisting Bulgarian jobseekers to work in Germany

The cooperation between EURES Germany and Bulgaria helped 208 jobseekers from Bulgaria to find a job in Germany from January to September 2013, mainly in vacancies that where hard to fill in the local labor market.

= 630 job vacancies on offer at European Job Day in Ireland

EURES Ireland recently organized a European Job Day in Dublin to help combat the high unemployment rates on the Emerald Isle.

= Helping cross-border workers

EURES also has an important role in advising and supporting cross-border workers. As an example, this is the case of a Belgian job seeker to find a position just across the German border.

= Engineers from Portugal find success in Norway

Over the past two years, an engineering group from Norway has employed eight Portuguese engineers via EURES services.

References: https://ec.europa.eu/eures/main.jsp?lang=en&catId=10609&myCatId=10609&parentId=20&acro=news&function=newsOnPortal,

= http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-14-22_en.htm?locale=en

= Improving EURES job search network: frequently asked questions (See also IP/14/26, MEMO/14/22).

Drive for industrial growth

Industry is of pivotal importance for the European economy. It produces four-fifths of all European exports and accounts for one third of all jobs in Europe, thus providing 57 million people with a livelihood. According to the EU leaders, the EU needs a strong industrial policy.

European industry is a global champion in many key areas: in automobile manufacturing, in mechanical engineering, in chemicals and pharmaceuticals. Moreover, the financial and economic crisis has shown that countries with a solid industrial survived better and they have less trouble finding ways out of crisis. For example, the European Parliament’s president, M. Schultz, underlined that the industry is a growth driver in Europe, generating positive spillover into other economic sectors. However, there are some problems facing the Union’s industrial policy, such as competition with other countries in the world (e.g. China has already become the world’s leading industrial nation while India, Brazil and Russia are catching up). Besides, production costs in these states are cheaper that in Europe.

Secondly, industries are re-locating jobs: more and more is being moved to countries outside Europe; according to the Commission, 3.5 million jobs have been lost since 2008.

Thirdly, rising energy prices across the EU states, the credit crunch, and insufficient investment in research and development have put even more pressure on European industry.

Therefore the EU member states must make sure that the innovative and sustainable products of the 21st century are designed and manufactured in Europe. This is the main message if Europe wants to maintain a competitive industry while keeping up with high social and environmental protection, if it wants to safeguard jobs, standard of living and generate further growth, argued EP’s president.

Strong industrial policy for Europe

An active European industrial policy was actually a primary vision even by the Communities’ “founding fathers”. The European integration process had its origins in the European Coal and Steel Community. On 9 May 1950, the French Foreign Minister, Robert Schuman, put forward a fascinating plan: coal and steel, the key war industries, would be placed under joint, supranational supervision.

This bold initiative bore fruit: the internal market grew out of the seed of the Coal and Steel Community, and for the last six decades, the continent has been living in a united, peaceful and prosperous Europe without borders.

However, in recent years, in developing the internal market the EU has focused on services, sometimes to the detriment of industry. European Commission during the period 2009-14 with Commissioner A.Tajani, responsible for this sector) was trying to put industrial policy back where it naturally belongs, i.e. on top of the European development agenda. He introduced an action plan for European “smart” re-industrialisation with some important steps to be taken in order to make fruitful such re-industrialisation.

Firstly, targeted investment in research and development is needed. Presently, Europe is lagging behind other major powers: the EU states spend about 2% of its GDP on research and development; in the USA, Japan, Canada, etc. the figures are over 3%.

European Parliament fought hard for the increase in the research budget during the 2014-20 MFF negotiations; the main message is that it is the European research policy that generates synergies and additional value.

Much needed flexibility can be generated via the new EU Horizon 2020 program too; otherwise, the member states risk losing many young talented scientists. Besides, Europe needs innovation more than ever in order to hold against global competition.

Secondly, the member states need targeted investment in infrastructure, e.g. in improving transport networks, in developing energy and broadband networks.

For example, one key instrument is the new funding mechanism under the EU’s Connecting Europe Facility for infrastructure projects; it is of joint interest in trans-European transport, energy and telecommunications. It aims of using about € 29.3 billion of EU budget for the next seven years to speed up the completion of trans-European networks.

Thirdly, in order to unlock the potentials of the EU industry, the member states must create an innovation-friendly environment, which means reducing the regulatory burden imposed by both the EU institutions and the national authorities.

The new Commission in place from the end of 2015 for the next 5 years wants to put all EU laws and regulations to the test if these laws suppress job creation and growth. Besides, the Commission’s task to complete the internal market means that regulatory complexities are holding back productivity gains. However, the idea is not to make industrial regulations less effective: the task is to create a climate of cooperation between business leaders and public authorities at all levels. These efforts could create in the member states a strong market for new economy products, and kick-start investment so that European companies are certain about the EU’s collective commitment.

Fourth, a strong industrial policy must be combined with an effective international trade strategy; the warning sign is that Europe, presently, has a negative trade balance. To guarantee market access for European products, to allow European companies to plug into the opportunities of emerging economies, the EU and the member states need a common trade strategy. For example, a free trade agreement between the EU and the USA (so-called, TTIP), would give a huge boost to growth and job creation on both sides of the Atlantic.

However, the EU leaders argued that such transatlantic partnership shall not be detrimental to the European “social market economy” and European high social standards.

In general, the EU must ensure that its external trade policies (being of the EU’s exclusive competence) make a genuine contribution to the sustainable and social development of the EU trading partners around the world.

That means that business community and actions of European corporations wherever they invest and/or operate should be in accordance with European values and internationally agreed norms.

Fifth point is to bring workers’ skills more into line with the needs of the economy. Today, there are five million young people out of work in the EU; however, at the same time, there are about two million unfilled vacancies. That means that European labour market does not have “the right” skills.

Increasing mobility in the internal market is only one recipe; primarily, the member states must improve workers’ skills as investing in people is paramount for keeping European industry sustainable.

Sixth point is about the member states’ obligation to support sustainable and resource-efficient industries. Energy is becoming increasingly expensive and raw materials increasingly scarce. One example – just 20% of costs come from labour, whereas 40% come from energy.

Hence, energy efficiency has a huge potential for cutting costs; Commission’s Eurobarometer published a report in mid-January 2015 showing that energy costs in Europe are twice as high as in the United States and 20 percent higher than in China.

Energy- and resource-efficient technologies are becoming a competitive advantage; therefore, the EU member states need “smart strategies” to exploit existing enormous potentials.

Seventh point is about boosting investments in the EU. Many countries are still struggling with the credit crunch. Investment is still below pre-crisis levels and countries need get back to those levels as quickly as possible, and ideally go further by improving the flow of credit to the real economy and targeting public spending.

Especially small- and medium-sized firms (SMEs) have difficulties in obtaining loans. However, there examples of prosperous firms that keep national economies afloat: between 2002 and 2010 small- and medium-sized firms created about 85% of all new jobs in the EU, particularly the start-ups.

The EU has already some new instruments like the European Investment Bank and COSME; the new EU program to improve access to finance for SMEs: for example, over 120 000 SMEs have benefited from EU programs during the last six years. Thus, the EU’s member states have to step up their efforts to develop innovative financial instruments.

Guiding prosperous industrial policy, the EU and the member states need to unlock

the industrial potential in Europe and implement “smart regulation” in the new

markets. That could be done with an increased role of state authorities: in particular,

public investment has the following roles:

= to stimulate demand – as some member states are doing with Advanced Broadband;

= to help finance the infrastructure- here the states should work more closely with the EIB;

= to improve the quality of training and apprenticeships; and

= to strive that research targets would create a “community of researchers” in the EU, the only way to attract and keep scientific talent.

References: = http://www.europarl.europa.eu/the-president/en/press/press_release_speeches/speeches/sp-2014/sp-2014-january/html/speech-at-business-europe-day, and

European member states are still far from the 20 percent target of industry’s share in the EU’s GDP by 2020. According to the European Commission report on the current status of EU industry, to meet this goal European states need re-industrialization, mainly through manufacturing sectors. It seems that the Baltic States’ developers should have the same agenda.

According to a European Commission report on the current status of EU industry (17 February 2014), most production sectors have still not regained their pre-crisis level of output and significant differences exist between sectors among the EU member states.

The analytical report has had a challenging title – "EU industrial structure report 2013: Competing in Global Value Chains". It has shown: a) the importance t of manufacturing sectors; b) that “internal” European consumption is not enough for progressive development; and c) the need for mutually beneficial links among manufacturing and services in Europe, as well as the importance of global value chains. The report ultimately underlines the growing need to mainstream industrial competitiveness into other policy fields.

These issues have been highlighted in the Commission's Communication on a European Industrial Renaissance and were the subject of the Competitiveness Council meeting in February 2014. The Commission was calling on the member states to support the new industrial compact at the Competitiveness Council.

Reference: European Commission, Press release, IP/14/150 “2013 industrial structure report highlights need for industrial renaissance”, 17/02/2014.

The main findings of the report. The

report showed that the fragile recovery hinted at by positive growth in 2010-11

was interrupted by a downturn in the business cycle and EU industries

experienced a double dip. It also confirmed that since 2001, manufacturing

sectors declined further by 3 percentage points, to around 15% of GDP in

2012 (as a proportion of economic output).

The main findings included the following assumptions:

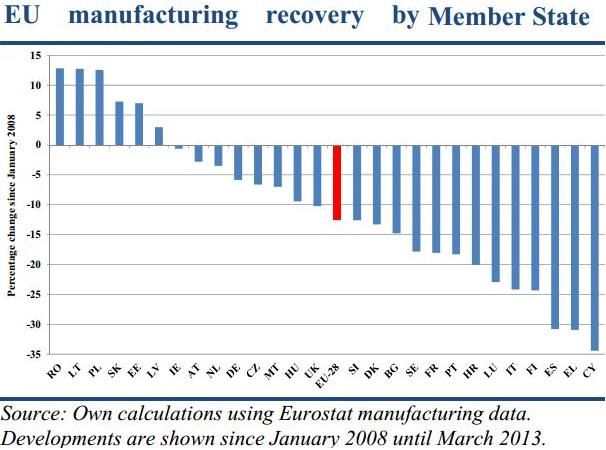

= Country differences. Overall EU manufacturing output masks significant differences between the EU member states. Strong recoveries can be seen in Romania, Poland and Slovakia; somehow the Commission is of the opinion that the Baltic States too regained and exceeded their pre-recession peaks.

= Sector differences. High tech, pharmaceuticals and staples (e.g. food and beverages) resisted crisis: there are also significant differences between sectors. Construction, manufacturing and mining industries were badly hit. Industries producing consumer staples such as food, beverages and pharmaceuticals, fared relatively better. High-technology manufacturing industries were not impacted to the same extent as other industries.

= Productivity gains. Differences vary, and are concentrated in high tech industries. Thus, productivity and employment gains varied significantly across sectors, with a general decline in manufacturing, in particular in low-tech industries. In the aftermath of the latest crisis, EU manufacturing managed to reduce labour costs and increase productivity, with high-tech industries as the main engine of growth. High-tech is being more resilient to the negative effect of the financial crisis thanks to both higher productivity and limited dependence on energy.

= The specialization in high-tech and low energy intensive industries is crucial for the strategic positioning of industries in the global value chain. This translates into above-average contributions to overall productivity growth and thus to real income growth. However, data on patent applications show that many high- and medium-tech industries in the EU still perform relatively poorly compared to the world aggregate and, in particular, the US. This lack of innovation threatens future gains in productivity.

= Services growing faster than manufacturing. On average, during 2000-12, market services (those typically provided by the private sector) grew by 1,7 percentage points in the EU, and now make up half of EU GDP. The share of non-market services (typically provided by the public sector) also increased, reaching 23% of GDP in 2012; hence, during 2001-10, employment grew in the service industries, whereas it declined in manufacturing.

= Links between manufacturing and services. These links are mutually

beneficial: the pharmaceuticals sector has experienced sustained growth since

the start of the financial crisis, while high technology manufacturing

industries (high-tech) have not been, generally, affected to the same extent as

other industries. Manufacturing firms are increasingly using services as part

of their business processes; in the development and sale of products, and for

horizontal business activities such as accounting and logistics. Higher

productivity growth in manufacturing can spill over to other sectors. The increased

interdependence between manufacturing and services implies a “carrier function”

of manufacturing for services that might otherwise have limited tradability.

The interconnections between manufacturing and services are growing, as

products are becoming more sophisticated and incorporate higher services

content.

A good example is the marketing of "smart" mobile phones which require the use of other services such as software applications (commonly known as "apps"), to maximize their usefulness. The app service providers would have a much smaller market without the access given by manufacturers of the app using devices. This carrier function also stimulates innovation and qualitative upgrading for service activities.

Through these linkages, higher productivity growth in manufacturing can spill over to service sectors. This is particularly important in view of the fact that, in the first decade of 2000’s, employment grew only in the service industries. Hence, a strong manufacturing sector can help mainstream competitiveness gains across other sectors of the economy. This has a stimulus effect on innovation and qualitative upgrading for service activities.

= Services are important for the competitiveness of manufacturing; growing share of services in GDP is explained by higher income elasticity of demand for services, which tend to shift final demand towards services, as incomes grow over time. Falling relative prices of manufacturing compared to services due to higher productivity growth in manufacturing also tend to reduce the relative share of manufacturing in nominal terms.

With respect to employment, the sectoral shift is even more pronounced, due to the fact, that services are more labour intensive and typically have lower productivity growth.

The inter-linkages between manufacturing and services are growing. Manufacturing firms’ use of intermediate services has increased across almost all industries since 1995.

= Manufacturing is changing from being dominated by machine operators and assembly line workers to a sector, which relies more and more on service occupations and service inputs. This shows up in the increased share of employees with services-related occupations, including activities such as R&D, engineering design, software design, market research, marketing, organizational design and after-sales training, maintenance and support services.

Analysis of trade in services indicates that the EU has a comparative advantage in almost all sectors except construction and travel. By comparison, the US economy has a comparative advantage in relatively few sectors (financial and insurance services and travel). Russia and China specialise in construction services, as does Japan. India is highly specialised in computer and information services, while Brazil exhibits high RCA (revealed comparative advantage) values in other business services.

= Global value chains and EU industry. The EU is still the largest player in

world trade, both in terms of goods and services and investment flows.

Globalisation has transformed firms’ ‘value chains’ through the creation of an

increasing number of established cross-border networks. While EU enterprises

are already involved in global value chains, strengthening their participation

will increase their competitiveness and ensure access to global markets in more

favourable competitive conditions.

The EU remains a leader in global trade; the importance of the EU single market to global trade figures is illustrated by export figures. Exports originating in EU-27 countries (Croatia was not part of the EU during the study period of the report), including intra-EU trade, accounted for 37% of total world exports in 2011.

Trade among EU countries represented 25 % of world-manufactured trade in 2011; by comparison, intra-regional trade in Asia reached about 17 % of world trade and in North America about 4%.

The EU is also the world's largest trading bloc. In 2010, EU exports to countries outside the EU accounted for 16% of world trade whilst about 25% of total world exports took place within the EU-28.

The EU has also a large share of world trade in manufactured goods: exports originating in EU-28 countries (including intra-EU trade) accounted for 37% of total world exports in 2011. In 2012 the EU, Asia and North America accounted for 78 % of total world exports in goods.

= World trade flows mostly involve developed countries. Most high‑income countries’ trade takes place with other high‑income countries. In all manufacturing sectors except textiles, paper, machinery, electrical equipment and basic metals, half or more of EU-28 exports are to high‑ income countries. The EU has largest world market shares in all industrial sectors (at the 2-digit level) except for computers, textiles, clothing and leather (where the leader is China).The highest market shares for EU manufacturing industries are in printing and reproduction of recorded media, tobacco, beverages, pharmaceuticals, paper and paper products and motor vehicles.

Some fast growing economic competitors are still dependent on high tech inputs from other countries.

China has comparative advantages in both high-tech and low-tech manufactures. However, while China has exported proportionally more technology-intensive goods in recent years, much of the content was imported from developed countries. Data on trade in value added confirms that the share of imported high-tech inputs is still higher in China than in the EU, especially for high-tech products.

EU-28 account for a significant proportion of global FDI flows (around 22 % of inflows and 30 % of outflows), but both inflows and outflows have been badly hit by the crisis. In 2010, EU FDI inflows were approximately a third of their 2007 level and outflows had fallen even further. Most of the fall in EU FDI inflows was due to a sharp drop in intra-EU flows since the start of the crisis.

= The EU is still the world leader in terms of global trade. The EU has comparative advantage in two-thirds of its exports. The EU needs to build upon its strengths to help reverse the trend of a declining contribution of manufacturing to national income, thus confirming the need to facilitate the internationalization and the integration of EU firms in global value chains.

Investment has fallen sharply and still focuses on finance and real estate. Industry needs investment.

Stocks of inward and outward EU FDI are concentrated in the financial and real estate sectors. Financial intermediation, real estate and business activities represent about three‑quarter of overall outward stock and about two thirds of inward stock.

Source: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-14-111_en.htm

= Latvian efforts: example. From the EU's long-term financial planning period

(2014-20), about € 500 million would be available for Latvian projects in

perspective research and innovation projects.

The

entire funding should not be invested in one sector. It is necessary to balance

sectors' financial appetite, explained Latvian Economy minister, Vjaceslavs

Dombrovskis.

There

are five “smart” specialization areas in Latvian “manufacturing” (in line with

the EU-2020 strategy), i.e. biomedicine, smart materials, information and

communication technologies, bio-economy and energy efficiency.

Each of these areas requires its own state support policy, assessing available technological specifics, business capacity, as well as scientific potentials.

The most optimal investment solution should be sought through a dialogue with other ministries, research institutions and scientific community, said Latvian minister.

For more information see:

= The full report "EU industrial structure report 2013: Competing in Global Value Chains" can be found at: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/industrial-competitiveness/competitiveness-analysis/eu-industrial-structure/index_en.htm;

= http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-150_en.htm, and

«The Baltic Course» Is Sold and Stays in Business!

«The Baltic Course» Is Sold and Stays in Business!