Analytics, Baltic States – CIS, Direct Speech, Economic History, EU – Baltic States, Port, Transport

International Internet Magazine. Baltic States news & analytics

Friday, 26.04.2024, 13:09

The Baltics and Europe

Print version

Print version |

|---|

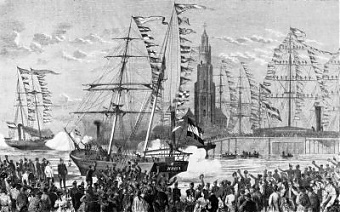

In the

Middle Ages, the Teutonic Order closed the access to the Baltic Sea for

Lithuania, therefore, Lithuanians acquired a geographically safe port as late

as in the 20th century and finally established their rights to it after the

Second World War, when Klaipėda went to Lithuania. The Baltic Sea, which

appeared in early historical sources under the name of Mare Suebicum, connected

Rome with the north of Europe through amber trade. Two thousand years ago,

Goths and Vandals dominated Baltic Sea area, gradually pushed by other tribes.

In the 10th through the 12th centuries, the Baltic Sea was divided into the

“spheres of influence” of Vikings, Veneti, Curonians, and Estonians. The

population of the Baltic Sea islands and coasts not merely fished and traded,

but also looted and pirated. In the 10th through the 13th centuries, Danes

actively represented their military and commercial interests in the Baltic Sea

and founded the city of Tallinn. Poland’s movement towards the coast was

blocked by the Teutonic Knights’ Orders who started the colonisation of the

Baltic region in the early 13th century. The Livonian Order founded the cities

of Klaipėda, Riga, and Ventspils. Although Klaipėda was located at the

intersection of active trade relations and covered the only safe and convenient

route between the Teutonic and Livonian Orders, it was a military city and

could take a more active part in trade as late as in the 15th century, when the

wars abated. In the 13th century, the first maritime trade-based empire, i.e.

the Hanseatic League, formed around the North and Baltic Seas. In the period

between the 13th and 17th centuries, the Hanseatic League connected almost 200

cities from Bergen on the Norwegian coast of the North Sea to Novgorod in

Russia.

It was a

united confederation with a common language, currency, and legal system, as

well as with strong civil traditions and individual rights. In Gothic, hansa

meant ‘a group of merchants’ whose governance and affiliation system was

somewhat similar to the European Union: it sought to have open borders, a

single currency, and a common, unified market that Europe had not yet seen. The

members of the League did not have any state borders and concentrated around

the towns, affiliated by common trade and city charters. Wealthy merchants of

the Baltic ports were fastidious consumers: they demanded the best Chinese silk

products, the best food and wine, they built churches and commissioned works of

art. Baltic seaports were noisy and lively places. Each port had its own

brewery. German port cities used to export their beer to Scandinavia and the

Baltic region; a sufficient amount, as a historian noted, so that every Swede would

be constantly tipsy. The reason for the prosperity of the Hanseatic and Baltic

ports was cheap transportation of goods between East and West. The cereals of

the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and of the Kingdom of Poland, salted Baltic

herring, Swedish timber and iron, Russian wax and furs were transported from

the East to the West. Lüneburg’s salt, Flemish woolen felt cloth, Rhine wine

and ceramics, and rolls of linen and wool from the cities of England and the

Netherlands were brought to the eastern Baltic ports from Western Europe. From

the 16th century, the competitive struggle for the profitable trade control

between East and West was joined by the Netherlands, who, due to an upturn in

fishing and commercial shipbuilding, felt a lack of suitable timber and other

raw materials. Via Klaipėda, ropes, cannabis, resin, potash, and raw material

for the rigging of ships were taken to Amsterdam, while the ships from the

Dutch ports transported barrels full of herrings. In the early 17th century,

when the dynastic war with the PolishLithuanian Commonwealth broke out, Swedes

appeared in the Baltic Region. Under the Truce of Altmark, in 1629, Klaipėda

together with other ports of Prussia went to Sweden for the period of six

years. The short Swedish rule (1629-1635) freed Klaipėda from its dependence on

Königsberg. Riga became the second city in Sweden that was to be declared its

capital. In the 17th century, Dutch ships were crossing the Baltic Sea and

making stops at the ports of Lübeck, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Riga, Klaipėda, and

Liepaja.

However,

the German influence in the Baltic did not disappear: not for nothing the

Flemish cartographer Gerhard Mercador called the Baltic Sea the German Sea.

Since the 18th century, after the influence of the Russian Empire on the Baltic

Sea had intensified, the competition between the empires and the seaports

controlled by them became increasingly fierce. Several fundamental changes in

the 20th century radically changed the significance of the Baltic ports. After

the Bolshevik revolution, St. Petersburg lost its exclusive role in the region,

since the Bolshevik power moved the capital city back to Moscow in the centre

of the state. The influence of Germans who had controlled the economy of the

south-eastern cities on the Baltic coast weakened. Upon separation from the

German Reich, Gdansk received the status of a free city and Klaipėda was

connected to Lithuania. Liepaja lost its role of a transit port: the capacities

of the port of Riga were sufficient to meet the economic needs of Latvia.

Before the Second World War, Riga was the fourth city in the Baltic region

after Stockholm, Leningrad, and Copenhagen. Klaipėda, controlled by Lithuanians

and the only Lithuania‘s gateway to the Baltic Sea, was economically developing

more actively than in the German times. At the end of the Second World War,

quite a few of the Baltic seaports turned into ruins. After the war, on the

Baltic coast from Leningrad to Wismar, the Soviet power was established, Pax

Sovietica. The German ethnicity almost disappeared from the demographic map of

the northern Baltic cities.

After the

war, thousands of chemical bombs were sunk in the Baltic Sea and still continue

to pose a significant threat. The Soviet Union-managed Baltic seaports had to

serve the imperial needs. Klaipėda became the main fishing port in the Baltic

Sea, while Cuban sugar, cereals, and coal were transported via Riga and

Tallinn. The pipeline laid to Ventspils pumped Siberian oil to the West, and in

Liepaja and Kaliningrad, Soviet Baltic naval bases were established Only after

the fall of the Iron Curtain, the port cities of the Baltic states – Klaipėda,

Riga, Ventspils, and Tallinn – regained their historical significance and

became important transit centres which account for a considerable part of the

budgets of the Baltic states. The ports undergo changes: Eastern Baltic

seaports turn from gloomy dock areas into attractive cities and, due to the

global communication and the economic growth of the Baltic states, the Baltic

Sea has all the opportunities to become a new Hanseatic Sea, the sea of

communication.

«The Baltic Course» Is Sold and Stays in Business!

«The Baltic Course» Is Sold and Stays in Business!