Editor's note

International Internet Magazine. Baltic States news & analytics

Saturday, 27.04.2024, 00:10

EU’s control over member states’ economic policies

Print version

Print version

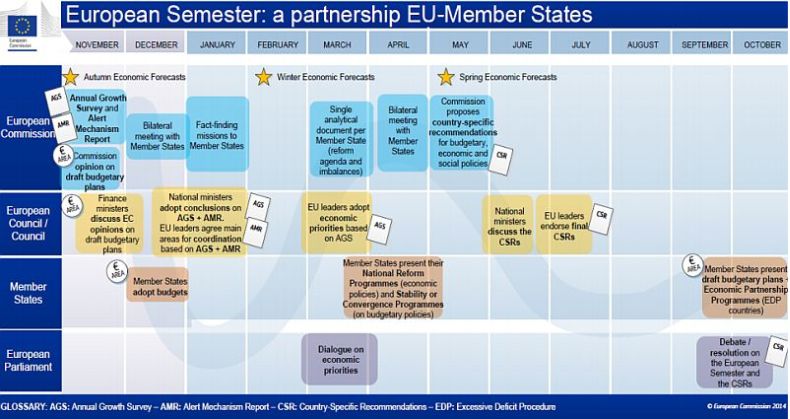

About three years ago, exactly in the fall of 2013, the Commission for the first time uncovered its plans to “control” the member states’ development policies in the form of a “semester”, in which such control has been called “partnership”.

In short, the scheme looks in the following way:

More on Semester: Modern EU Policies: Integration in Action

New economic progress

According to the Commission, the European Semester process is the key vehicle to focus the EU states' attention on their most important socio-political challenges. Gradually, the European Semester takes a more central role also in domestic policy debates on fiscal and macroeconomic challenges.

The EU’s approach to creating new economic progress is built on the 3-way approach. This means: a) boosting investment, b) pursuing structural reforms to modernise member states’ economies, and c) continuing fiscally-responsible policies.

The magic “economy-progress” wheel looks in the following way:

Changes in the semester

Main instrument in implementing economic coordination are the so-called “country reports”, i.e. country-specific recommendations issued by the Commission.

In contrast to the previous scheme, where the countries’ reports were issues in May, the new structure makes these reports for the member states available already at the end of February, so-to-say at the initial stage of the states’ political decision process for a year to come.

The reports will serve as the basis for discussion with the member states of their national policy choices and priorities ahead of their National Programmes in April 2016, and will lead to the formulation in late spring of the Commission's Country-Specific Recommendations.

Early publication of the “country reports” in February (see: Country Reports) is part of the efforts to streamline and strengthen the European Semester, in line with the Five Presidents' Report and the steps announced by the Commission to complete Europe's Economic and Monetary Union.

Such report-recommendations from the Commission are carefully screened by two leading EU institutions: the Council of Ministers (an “assembly” of the member states’ sectoral ministers) and the European Council (as the summit of EU head of states/governments). Besides, and this is additionally important, these recommendations are taking the form of “control”, as they have to be approved at the national level: either by the governments or/and the parliaments.

This

“directive-kind” approach towards “deeper coordination” of member states’

policies has a mildly-said mixed reaction in EU-28, despite the fact that these

recommendations go through a very thorough adoption process among the legally

fixed EU institutions.

European Semester’ perspectives

The Commission is obliged within the European Semester structure to pursue a close dialogue with the EU member states: thus, in March, the Commission will hold bilateral meetings with the states on “country reports”.

Commissioners will also visit states to meet national governments, parliaments, social partners and others. In return, the EU states are required to present in April their National Reform Programmes and their Stability Programmes (for euro area countries) or Convergence Programmes (for non-euro area countries), covering public finances.

The Commission has called on EU states to consult closely national parliaments and the social partners when preparing these documents. The Commission will then present its proposals for a new set of Country-Specific Recommendations in spring, targeting the key economic and social priorities for each country.

Also in March 2016, the Commission will decide on the Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure (MIP) category for each EU state covered by an In-Depth Review. Beginning with 2016, the Commission has reduced MIP from six to four categories of macroeconomic imbalances, i.e. a) no imbalances, b) general imbalances, c) excessive imbalances, and d) excessive imbalances with corrective action.

“Coordination” vs. sovereignty

Talks about EU’s control over national development have ability to change political life in the member states. Thus, the role of the national parliaments in “political economy” becomes crucial: the national parliaments would undergo “inner evolution” to become more intensively and more regularly involved in the national decision-making process and national practices.

During last months, the Commission has already had constant and detailed discussions with national parliaments, social partners and other “actors” in this regard.

However, some states are very worried about being “stronger, safer and better off” in the EU; possible vote to leave the EU won’t just damage Britain’s economy, imperil its security, and potentially break up the UK, the Economist (27 February 2016) argued in an editorial in one of the latest issues.

Since D. Cameron first promised an in/out referendum in a speech at the London office of the Bloomberg news agency in January 2013, there has usually been a clear lead for staying in.

Just to note, there is no precedent aside from Greenland to leave the EU; it left the club in 1985, but it is a “tiny feature” and the territory remains a dependency of Denmark, which is in the EU.

The UK’s assumption is that a vote for Brexit would trigger an application to withdraw under article 50 of the Lisbon treaty. See: http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21693568

The most important change D. Cameron wanted was a

guarantee that the bigger euro-zone block could not force changes in non-euro

countries. The 19-strong euro area, where decisions are made according to “weighted

votes” (according to the size of countries), now has the power to legislate for

the entire EU. Cameron (after the February summit) has secured agreement for

enhanced observer status for non-euro countries in euro-zone meetings and an

understanding that a non-euro country can appeal to an EU summit if it objects

to decisions taken at such meetings.

The most heated argument at the summit came over Cameron’s desire to stop new EU migrants to Britain from claiming in-work benefits for four years, and to cut the level of benefits paid for children whom they have left in their home countries. As a compromise, he secured an “emergency brake” that will let Britain delay paying benefits for a seven-year period and cut child benefits for existing migrants after 2020.

East Europeans are unhappy with these changes, argued the Economist; yet they seem unlikely to reduce the numbers of EU migrants, since most come to Britain to work, not to claim benefits.

However, several EU states’ leaders were hostile to Cameron’s insistence on an exemption for Britain from the EU’s goal of “ever closer union”.

http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21693569

The UK’s exit would also be a terrible result for the EU and the West generally. “It would uncouple the world’s fifth-largest economy from its biggest market, and unmoor the fifth-largest defence spender from its allies. Poorer, less secure and disunited, the new EU would be weaker; the West, reliant on the balancing forces of America and Europe, would be enfeebled, too” argued B. Johnson, London’s major. He added that such arguments are tempting; hence, the EU needs to start preparing for a possibility of a Brexit.

At the EU summit in mid-February, Janis A. Emmanouilidis, Director of Studies at the European Policy Centre mentioned that “a rather positive deal was finally struck” meaning that after hours of strained negotiations, British PM David Cameron managed to convinced other EU leaders to accept his proposals for a reform. Back in November 2015, D. Cameron sent a fourfold list of settlement proposals to D. Tusk, President of the Council of the EU, aimed at encouraging the UK to remain in the EU. When one looks at the final outcomes of the discussion, it is clear that Cameron got most of what he asked for, especially on issues with respect to decisions taken in the euro-area. But these negotiation outcomes are but the tip of the iceberg for Cameron who needs to convince the British electorate that, not only should the UK stay in the EU, but also that it will be beneficial for both parties. The UK Referendum is to take place on 23rd June 2016.

Brexit: myth busting. Former British

Europe minister Denis MacShane takes explained three myths surrounded Brexit:

first myth that Brexit cannot happen: he said that it was very possible that it

would; second is that negotiations for a future outside the EU would be

relatively painless: he thinks that that is “highly unlikely”, and third,

that the referendum will settle the question of Europe once and for all: he

thinks that regardless of whether Britain would vote to stay or leave the EU in

June, “the forces pulling Europe apart will begin to accelerate”.

The Czech prime minister, B. Sobotka (in the seat from the end of January 2015) warned that a British exit from the EU could influence his country to follow suit. “Debates about leaving the EU could be expected in this country in a few years, too, if Britain left the EU,” Bohuslav Sobotka said.