All rights reserved.

You may not copy, reproduce, republish, or otherwise use www.baltic-course.com content

in any way except for your own personal, non-commercial use.

Any other use of content requires the hyperlink to www.baltic-course.com.

Printed: 06.07.2025.

PrintEmployment and Social Development in EU: new analysis

PrintEmployment and Social Development in EU: new analysis

The ESDE review reports on the latest employment and social trends, and reflects on upcoming challenges and possible policy responses. Based on the latest data and literature available, the review underpins the Commission's initiatives in the employment and social policy field, feeding into the European Semester, the Mobility Package, the Skills Package and the development of the European Pillar of Social Rights.

Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs, Skills and Labour Mobility, Marianne Thyssen, commented on the report published that the report’s idea was to ensure that there are more and better opportunities for people in the EU, especially those furthest away from the labour market. She underlined that the member states need also invest in enhancing people's skills, so that all women and men in the EU can realise their full potential.

Invest in people achieves additional growth and jobs, thus ensuring that the labour laws and social protection systems in the EU-28 are fit-for-purpose in the 21st century, coped with fostering entrepreneurship and innovation. In this sense, the European Pillar of Social Rights will play an important role, she added.

However, despite recent improvements, huge disparities still exist among the EU states, in terms of economic growth, employment and other key social and labour market indicators. Many of these disparities are linked to an under-utilisation of human capital on several fronts.

The 2015 ESDE report looks at ways of tackling existing disparities, focusing in particular on job creation, labour market efficiency, social protection modernisation and investment in people.

Promoting job creation

The ESDE 2015 review highlights the potential of self-employment and entrepreneurship to create more jobs. However, the data suggests that some groups, including young people, old people, women, and ethnic minorities, may face stronger barriers to start their own businesses. In addition, this year's report indicates that a majority of people do not feel that they possess the necessary skills or knowledge to start a business. The ESDE review reveals that targeted policies can help. These can include easier access to financing or fiscal incentives, entrepreneurship education or access to child and elderly care.

The ESDE review also reports an increase in the variety of employment contracts, which allow for flexible working arrangements and therefore increased labour market participation, but can also lead to labour market segmentation. While some new contracts offer a potential win-win situation, others bring about work uncertainty. Flexibility is important, but security is also needed – an issue that will also be addressed in the context of developing the European Pillar of Social Rights.

Improving labour market efficiency

The 2015 ESDE review reveals that the EU can make better use of its human resources through mobility. Although the number of mobile workers has increased over the past two decades, their share in the total work force remains limited: Only 4% of the EU's population aged 15 to 64 live in a Member State other than the one they were born in. Yet, mobile EU workers tend to have better employment prospects overall than the native population. In addition, their flows have reduced unemployment in some Member States hit hardest by the crisis and helped address staff shortages in receiving countries. The ESDE review therefore clearly underlines the economic potential of mobility.

The review also looks at long-term unemployment, which affects about 11.4 million people in the EU. Fighting long-term unemployment is crucial when striving to improve labour market efficiency, as the long-term unemployed have about half the chance of finding employment compared to the short-term unemployed. The analysis in the ESDE review shows that being registered with national public employment services and participating in training, significantly increases the chances of moving to a sustainable job. The Recommendation on long-term unemployment adopted by the Council on 7 December 2015 is in line with these findings.

Finally, social dialogue will be crucial in promoting a sustainable and inclusive economic recovery. Social partners have been involved in the design and implementation of several major reforms and policies. For social dialogue to play this role effectively, the capacity of social partners needs to be strengthened, particularly in Member States where social dialogue is weak or has been weakened due to the economic crisis.

Investing in people

Although the level of unemployment in the EU remains high, employers continue to encounter difficulties in filling certain vacancies. In addition to genuine mismatches in skills, the ability to fill vacancies is also limited by an inability to offer attractive pay or working conditions, good training or career opportunities. The ESDE 2015 review finds that there is a significant share of non-EU workers in occupations below their qualification level. The New Skills Agenda initiative that the Commission is preparing for this year will seek to address these challenges. In addition, employment levels of women with children and older workers are still significantly low. Promoting greater labour market participation of these groups will be crucial in the context of an ageing population.

Reference: European Commission, press release “2015 Employment and Social Developments review: Investing in people is key to economic growth”, Brussels, 21 January 2016, in:

Employment and Social Developments in Europe: main aspects

The review underpins the Commission's initiatives in the employment and social policy field, feeding into the European Semester, the Mobility Package, the Skills Package and the development of the European Pillar of Social Rights.

1. Promoting job creation

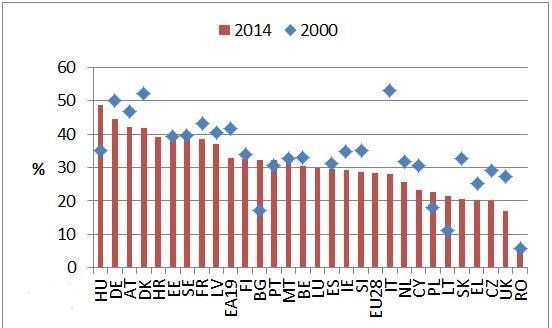

About 16% of all employed people in the EU are self-employed. Out of these 16%, more than two thirds are solo self-employed, though their share varies across Member States. Micro-enterprises of less than 10 employees account for around 30% of all EU employment, of which nearly a third is in the wholesale/retail and motor vehicle and motorcycle repair sectors. In several Member States, a significant share of those self-employed is employed in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sectors. Promoting self-employment and entrepreneurship has the potential to create jobs and give unemployed and disadvantaged people an opportunity to fully participate in society and the economy.

However, national policies can encourage starting a business or help

the self-employed to hire employees. Survey

data points to significant bottlenecks in stimulating self-employment and

entrepreneurship. In 2014, less than 50% of 18-64 year olds in the EU

believed that they possess the necessary skills and knowledge to start a

business. In addition, only 16% of all employed are self-employed and on

average, less than one third of the self-employed hire employees, though there

are strong differences across Member States.

|

| Share of self-employed who engage employees |

Source: DG EMPL calculations based on Eurostat, EU-LFS Note: from 15 to 64 years.

Labour market policies together with other policies (product market regulations for example) can encourage starting and expanding a business and help the self-employed hire employees. These include:

· entrepreneurial skills formation is crucial to identify and exploit new opportunities, and manage growth

· lowering hiring and firing costs

· improving the flow of information about job vacancies across Europe

· improving access to finance: e.g. diversifying systems of funding

· strengthening business support services: e.g. better access for disadvantaged groups

· reducing the regulatory burden

· giving a second chance: e.g. by tackling the stigmatisation of honest bankruptcy

· adjusting tax regulation and access to social protection, notably to health care, childcare and elderly care facilities

However, the share of women in self-employment is significantly lower than that of men. Women cover only about one third of total self-employment. Specific barriers for women include:

· maintaining a good work–private life balance (e.g. via well-designed child-support facilities),

· less favourable credit terms,

· low participation rates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education,

· conducting business in strong male-orientated business networks,

Some other groups, such as young people, older people and ethnic minorities may also be facing strong barriers to starting and expanding a business.

|

| Share of women among self-employed |

Source: DG EMPL calculations based on Eurostat

Labour legislation in support of job creation

Labour market segmentation refers to the existence of different groups of workers who may face different working conditions, such as working hours, contract insecurity, wages, access to promotion and career opportunities, or access to health care or pensions.

The 2015 ESDE review indeed observes a segmentation of labour markets, which is being reflected by the large use of temporary and involuntary temporary contracts, short employment spells alternated with unemployment spells, low transitions from temporary to permanent regular contracts, high shares of involuntary part-time contracts, and low levels of on-the-job training. In addition, there has been a recent rise in ‘economically dependent work’ or involuntary self-employment, whereby workers do not have a contract of employment but provide goods and services to a main or single client on whom they depend for activity and source of income. Although some new contracts offer a potential win-win situation, others raise serious concerns as they bring about work uncertainty, fewer working hours, less social protection and lower autonomy in work decisions. Both flexibility and security are needed.

Employment protection legislation (EPL) is broadly defined as the set of legal rules and procedures that define the limits to the ability of firms to hire and fire workers in private employment relationships. EPL is enshrined in labour law and in collective and individual labour contracts. Its aim is to protect workers from arbitrary action by employers and to protect workers and society from the costs and risks associated with job dismissal, especially in a context of limited alternative protection against unemployment risks.

On one hand, employment protection legislation can contribute to job stability, potentially increasing worker's motivation and productivity. On the other, it may imply higher hiring and firing costs, which can reduce companies' ability to adjust to technology or economic shocks and, as a consequence, not help reduce unemployment.

Differences in employment protection legislation for different types of contracts may generate segmentation, with firms potentially preferring more flexible contracts that can involve lower costs. This, however, can have negative implications for employment transitions into permanent employment and for motivation, human capital, productivity and growth.

2. Labour market efficiency

Long-term unemployment refers to people who have been out of work for over a year and affects about 11.4 million people (about 5% of the active EU population). About two thirds of them (7 million) have been out of work for more than two years. More information can be found here: See IP/15/5565

The longer people are out of work, the more problematic it is to return to a job and the more likely it is to become inactive. And inactivity is a challenge in the context of an ageing population, as the working-age population starts to decrease. Long-term unemployment and inactivity can also lead to lower earnings, poverty and exclusion.

Even as economic growth continues to picks up, the improvements regarding long-term unemployment have been very modest. This is due to the fact that exit rates from long-term unemployment tend to be less sensitive to upturns in the economic cycle than those of the short-term unemployed, because of their unfavorable labour market characteristics (e.g. low-skilled) and therefore their lower employability. This then turns long-term unemployment into a structural rather than just a cyclical challenge, with the risk of those affected becoming discouraged and falling into inactivity just at a time when Europe's working-age population starts to shrink and it becomes increasingly important for the EU economy to make the maximum use of all its potential labour resources.

This is why it is important not to rely on economic recovery alone to reduce long-term unemployment. The Council Recommendation on the integration of the long-term unemployed adopted on 7 December 2015 calls on Member States to step up their action in this area (see IP/15/5565).

= Policies to get the long-term unemployed back to work

Policy interventions with a major positive impact in aiding the long-term unemployed back to stable jobs are three-fold: 1) lifelong learning/training, 2) registration with public employment services and 3) receiving unemployment benefits. The impact of the last two policy interventions depends, however, on their design and quality of their delivery, and the outcome can vary across target groups.

Comprehensive policy action is needed, combining activation and support that is linked to the economic cycle, extending both expenditure and coverage of support (e.g. unemployment benefits) and activation measures (e.g. active labour market policies and lifelong learning/training) during economic downturns. Searching and job assistance services can also help the long-term unemployed finding a job.

Group-specific and country-specific policy interventions remain key to helping the long-term unemployed get back into stable jobs.

= Mobility and Migration

Europe's working-age population has started to decline, and the decline is expected to continue over the next decades. In parallel, the EU's economic growth has been sluggish compared to its main global competitors. To improve the EU's future growth perspective, the Union has to focus on increasing productivity growth and tapping into all sources of employment growth. Both intra-EU mobility and third-country immigration can help to achieve these aims.

Mobility can and has helped reducing unemployment in Member States hit hard by the crisis, providing resources for Member States that needed workers. If temporary, mobility can help improve the skills and competences of mobile workers who return to their countries of origin. In addition, third country migration cushions to some extent the impact of the workforce decline. In both cases, qualification is a necessary condition and will support higher growth. If well integrated, highly qualified mobile people and migrants will improve the total workforce's qualification mix in the host country, thereby increasing labour productivity, employment, and growth in the long run.

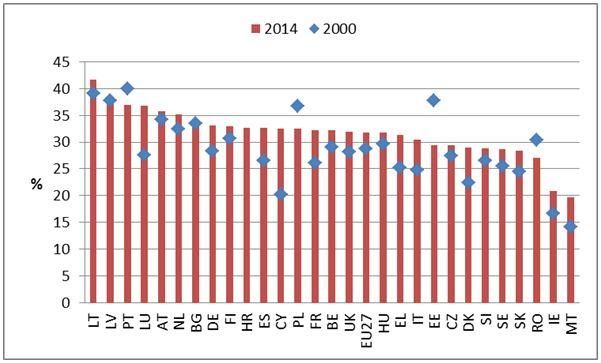

In 2014, the share of EU mobile people in the EU's total population was less than 4%, the share of third-country migrants was roughly twice as high. Mobility can be an important source of additional growth: As people move to other Member States in search of better working opportunities, they improve both employment and productivity growth throughout the EU.

|

| Mobile EU people and third-country migrants in the EU, 2014 |

Source: Own calculations based on EU-LFS. EU aggregates include estimates for DE, based on demographic statistics and the EU LFS (based on nationality).

Mobile EU people (i.e. people born

in the EU moving to another EU Member State) tend to be younger and better

educated, and they tend to move to countries where unemployment is low. These

characteristics allow them to perform better on the labour market. Compared to

those born in their country of residence, the chance of being employed is

therefore much higher for mobile people born in the EU-15 (the 15 Member States

before the 2004 enlargement) and the EU-10 (the 10 Member States which joined

in 2004).

Mobile EU people's and migrants' higher formal education is a necessary condition for higher growth, yet research shows that it is not sufficient. Both groups often fail to capitalise on their higher education. This is either because of limited labour market access or because they lack host-country-specific skills, for example language. As a result, they face labour market barriers, accept lower wages, work in low-growth or declining sectors or work below their formal level of education. To address this, greater investment is needed in improving skills as they are an important lever for capitalising on (formal) education. Acceptance of existing formal education by employers also needs to be strengthened and discrimination needs to be tackled. And finally, formal barriers to the labour market should be removed.

= Social dialogue:

Social dialogue, which refers to the interaction between the representatives of workers and employers, is an essential part of the European social model and a prerequisite for a well-functioning social market economy. Workers' and employers' representatives are uniquely well-placed to anticipate and address challenges in the world of work, and to find balanced solutions that enjoy a broad ownership and support.

In line with the Treaty, the European Union recognises and promotes the role of the social partners at its level, taking into account the diversity of national systems, and respecting their autonomy. The ‘New start for social dialogue’ launched under the Juncker Commission aims at improving the involvement of social partners in the European Semester, as well as stepping up their contribution to EU policy- and law-making. (See IP/15/4542)

There is a large diversity of national systems of social dialogue, which the EU must respect according to Treaty provisions. Still, a number of common key factors can be identified and compared across countries. Social dialogue relies on strong social partners with a broad membership base and capacity to speak on behalf of workers and employers. Membership rates of employers' organisations and trade unions differ substantially across Member States. Moreover, certain categories are consistently less likely to be organised (the young or those on fixed-term contracts among workers, and small- and medium-sized enterprises among employers).

Trust and a climate of cooperation between workers and employers is a further important precondition for an effective social dialogue. However, Member States that are perceived as having the most cooperative labour relations are not necessarily those with the lowest rates of industrial conflict (strikes or lock-outs).

3. Removing obstacles to job creation

= Human Capital/Skills. The fast-changing economy of today, with ever stronger knowledge and innovation components, is rendering people’s skills obsolete more quickly than ever before. Demand for entirely new sets of skills is emerging. This imposes new requirements on workers, employers, policy-makers and research. Workers need to upgrade their skills to adjust to changing demands. Employers need, and are expected to offer, good training opportunities for workers and modernise their recruiting and HR policies. Governments must invest in education and training for skills and implement instruments that foster their development; this requires a long-term perspective, based on predictions from research about the likely future labour market demand. The attainment of high-quality and relevant formal qualifications is also needed, along with mechanisms for the validation of workers' non-formal and informal learning. Engaging adults in education or training represents untapped potential for better employability. On EU level, the European Commission will present its New Agenda for Skills in the course of 2016.

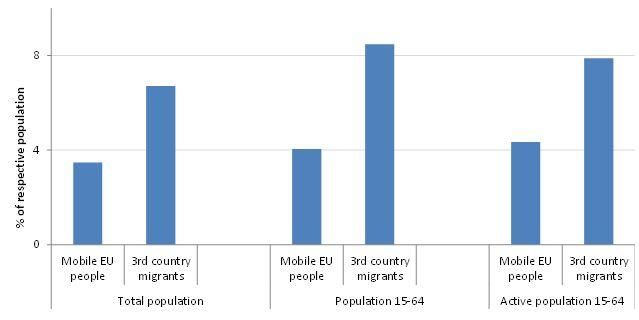

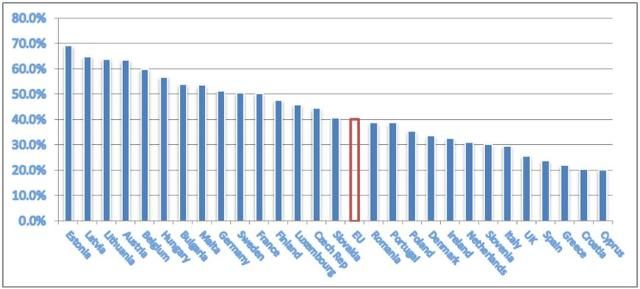

Four out of ten firms in the EU reported difficulties finding staff with the right skills – in spite of the unprecedentedly large pool of unemployed people available to them. This is the result of the latest European Company Survey carried out in spring 2013. As is shown in the chart below, these skill shortages vary markedly across EU Member States. Over 60% of establishments in Austria and the Baltic states have difficulties finding suitably skilled employees, compared to less than 25% in Croatia, Cyprus, Greece and Spain.

|

| Difficulties finding staff with required skills in European firms*, 2013, EU-28 |

Source: Third European Company Survey (2013), Eurofound 2013c.

* Proportion of establishments replying affirmatively to the question ‘Did your establishment encounter difficulties in finding staff with the required skills?’

= Social protection. Countries like the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark and Slovenia are characterised by high employment rates of mothers as well as low child poverty rates, low material deprivation among children and a good relative income situation of families with children. Compared to the EU average, these countries also have more small children in childcare, a more equal use of childcare services across the income distribution, spend more on family benefits, have shorter than average maternity leave and have more mothers working part-time.

While part-time work can be a good

option for working parents to combine more easily a professional career and

childrearing, it might not always be a sufficient source of income (part-time

workers have a higher risk of poverty). It also leads to inferior training

opportunities, poorer career prospects and, ultimately, lower pension

entitlements. Indeed, almost a third of part-time workers in the EU are in this

situation involuntarily. Women in particular declare care responsibilities as

the main reason for working part-time. Better sharing of care responsibilities

between mothers and fathers, access to quality childcare services and flexible

working time arrangements are ways to promote gender equality in the labour

market and mothers' work outside home. Some countries, like Denmark and Slovenia,

show that it is possible to combine high employment rates of mothers and high

shares of mothers working full-time.

Labour market situation of older workers since the crisis

Improvements in the labour market attachment of older workers continued almost everywhere in the EU during the crisis. However, transitions remain less dynamic for older people compared to the rest of the working-age population. In particular, new hires of older people are relatively scarce, particularly in countries with low employment rates of older workers.

Reference: European Commission, Fact sheets: “2015 Employment and Social Developments in Europe Review: frequently asked questions”, Brussels, 21 January 2016. In:

http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-16-92_en.htm?locale=en;

= See also IP/16/93.